Isfahan

An ancient town and capital of Persia from 1598 to 1722.

Iran’s Hidden Jewel

An ancient town and capital of Persia from 1598 to 1722.

Isfahan (or Es·fa·han (ĕs’fə-hän’, Persian: اصفهان) is a city in central Iran, about 450km south of Tehran.

The Persians call it “Nesf-e-Jahan”, meaning “Half of The World” mainly because of its beautiful hand-painted tiling and magnificent public square.

Four hundred years ago, Isfahan was larger than London and more cosmopolitan than Paris.

It is long noted for its fine carpets and silver filigree and today, textile and steel mills is bolded. Its architecture, tree-lined boulevards, and relaxed pace make it one of the highlights of Iran.

The city enjoys a temperate climate and regular seasons.

It is similar to Denver in the United States in terms of altitude and precipitation.

Isfahan is the twin city of Freiburg and Freiburg Street in Isfahan is famous.

It’s so delightful when you are in the shadow of the Imam Mosque and bathed in the soothing sounds of traditional music, sitting cross-legged on wide benches and feast on Dizi (an intricate Persian dish).

Naqsh-e Jahan (Imam) Square

Hemmed on four sides by architectural gems and embracing the formal fountains and gardens at its center, this wondrous space is a spectacle in its own right. It was laid out in 1602 under the reign of the Safavid ruler, Shah Abbas the Great, to signal the importance of Esfahan as a capital of a powerful empire. Cross the square on a clear winter’s day and it’s a hard heart that isn’t entranced by its beauty.

At 512m long and 163m wide, Naqsh-e Jahan is one of the largest squares in the world, earning a listing as a Unesco World Heritage site. The name means ‘pattern of the world’ and it was designed to showcase the finest jewels of the Safavid empire – the incomparable Masjed-e Shah, the elegant Masjed-e Sheikh Lotfollah and the lavishly decorated Kakh-e Ali Qapu and Qeysarieh Portal.

The square is at its best in late afternoon when the blue-tiled minarets and domes are lit up by the last rays of the sun and the mountains beyond turn red.

Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque

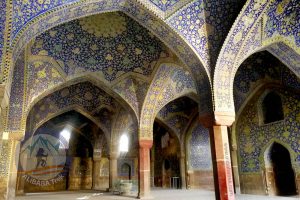

Punctuating the middle of the arcades that hem Esfahan’s largest square, this study in harmonious understatement complements the overwhelming richness of the larger mosque, Masjed-e Shah, at the head of the square. Built between 1602 and 1619 during the reign of Shah Abbas I, it was dedicated to the ruler’s father-in-law, Sheikh Lotfollah, a revered Lebanese scholar of Islam who was invited to Esfahan to oversee the king’s mosque (now the Masjed-e Shah) and theological school.

The dome makes extensive use of delicate cream-colored tiles that change color throughout the day from cream to pink.

The pale tones of the cupola stand in contrast to those around the portal, which displays some of the best surviving Safavid-era mosaics.

The mosque is unusual because it has neither a minaret nor a courtyard, and because steps lead up to the entrance. This was probably because the mosque was never intended for public use, but rather served as the worship place for the women of the shah’s harem.

Inside the sanctuary, the complexity of the mosaics that adorn the walls and the extraordinarily beautiful ceiling, with its shrinking, yellow motifs, is a masterpiece of design.

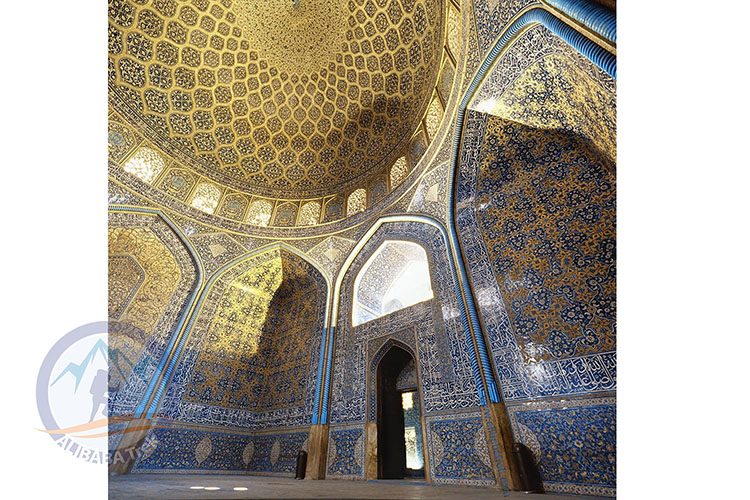

Imam Mosque

This elegant mosque, with its iconic blue-tiled mosaics and its perfect proportions, forms a visually stunning monument at the head of Esfahan’s main square. Unblemished since its construction 400 years ago, it stands as a monument to the vision of Shah Abbas I and the accomplishments of the Safavid dynasty. The mosque’s crowning dome was completed in 1629, the last year of the reign of Shah Abbas.

Although each of the mosque’s parts is a masterpiece, it is the unity of the overall design that leaves a lasting impression, and the positioning of the much-photographed entrance portal is a case in point as it has more to do with its location on the square than with the mosque’s spiritual aims. The portal’s function was primarily ornamental, providing a counterpoint to the Qeysarieh Portal at the entrance to the Bazar-e Bozorg.

Although the portal was built to face the square, the mosque is oriented towards Mecca, so a short, angled corridor was constructed to connect the square and the inner courtyard, thereby negating any aesthetic qualms about this misalignment.

Ali Qapu Palace

Built at the very end of the 16th century as a residence for Shah Abbas I, this six-storey palace also served as a monumental gateway to the royal palaces that lay in the parklands beyond (Ali Qapu means ‘Gate of Ali’). Named after Abbas’ hero, the Imam Ali, it was built to make an impression, and at six storeys and 38m tall, with its impressive elevated terrace featuring 18 slender columns, it dominates one side of Naqsh-e Jahan (Imam) Sq.

The terrace affords a wonderful perspective over the square and one of the best views of the Masjed-e Shah and the mountains beyond. The attractive wooden ceiling with intricate inlay work and exposed beams has been painstakingly restored and now attention is turning towards the walls.

Many of the valuable paintings and mosaics that once decorated the 52 small rooms, corridors and stairways were destroyed during the Qajar period and after the 1979 revolution. Fortunately, a few fine examples remain in the throne room off the terrace, but the real highlight of the palace is the music room on the upper floor.

Chehel Sotoun Palace

Built as a pleasure pavilion and reception hall, using the Achaemenid-inspired talar (columnar porch) style, this beautifully proportioned palace is entered via an elegant terrace that perfectly bridges the transition between the Persian love of gardens and interior splendor. The 20 slender, ribbed wooden pillars of the palace rise to a superb wooden ceiling with crossbeams and exquisite inlay work. Chehel Sotun means ‘40 pillars’ – the number reflected in the long pool in front of the palace.

The only surviving palace on the royal precinct that stretched between Naqsh-e Jahan (Imam) Sq and Chahar Bagh Abbasi St, this Safavid-era complex is reputed to date from 1614; an inscription uncovered in 1949, however, says it was completed in 1647 under the watch of Shah Abbas II. Either way, the palace on this site today was rebuilt after a fire in 1706.

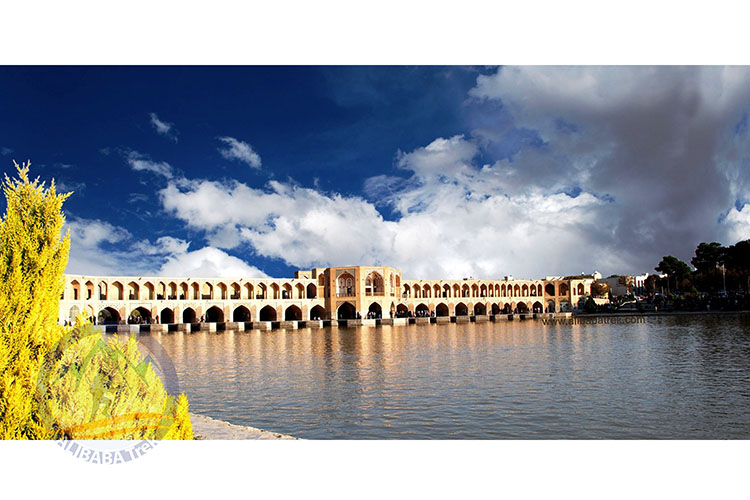

Si-o- se-Pol Bridge

The 298m-long Si-o-Seh Bridge was built by Allahverdi Khan, a favourite general of Shah Abbas I, between 1599 and 1602. It served as both bridge and dam, and is still used to hold water today. It is a popular meeting place when people gather to watch the sunset and catch a romantic moment under the arches.

Khaju Bridge

Arguably the finest of Esfahan’s bridges, with traces of the original paintings and tiles that decorated its double arcade still visible, Pol-e Khaju was built by Shah Abbas II in about 1650, but a bridge is believed to have crossed the waters here since the time of Tamerlane. The bridge is as much a meeting place as a bearer of traffic and at nighttime Esfahanis gather under the arches to sing: those with the most convincing voices (or indeed songs) attract sizeable crowds.

The bridge also doubles as a dam with locks in the lower terraced arcade regulating water flow. When the river is full, the sunset from the middle of the bridge is a fine sight – so good, in fact, that a pavilion was built here exclusively for the pleasure of Shah Abbas II.

Grand Bazaar

One of Iran’s most historic and fascinating bazaars, this sprawling covered market links Naqsh-e Jahan (Imam) Sq with the Masjed-e Jameh. At its busiest in the mornings, the bazaar’s arched passageways are topped by a series of small perforated domes, each spilling shafts of light onto the commerce below. While the oldest parts of the bazaar (those around the mosque) are more than a thousand years old, most of what can be seen today was built during Shah Abbas’ ambitious expansions of the early 1600s.

The bazaar is a maze of lanes, madrasehs, khans (caravanserais) and timchehs (domed halls or arcaded centers of a single trade, such as carpet vendors or coppersmiths). It can be entered at dozens of points, but the main entrance is via the Qeysarieh Portal at the northern end of Naqsh-e Jahan (Imam) Sq.

Cool in summer and warm in winter, it’s easy to lose half a day wandering the bustling lanes of the bazaar, sniffing the heaps of layered spices and dishes of dried dates, watching shoppers finger coloured lengths of material, and pausing to admire the rows of red and white teapots in the many crockery shops. Teahouses help punctuate the walk and a biryani restaurant is a perfect place for lunch.

Jame’ Mosque

The Jameh complex is a veritable museum of Islamic architecture while still functioning as a busy place of worship. Showcasing the best that nine centuries of artistic and religious endeavor has achieved, from the geometric elegance of the Seljuks to the more florid refinements of the Safavid era, a visit repays time spent examining the details – a finely carved column, delicate mosaics, perfect brickwork. Covering more than 20,000 sq meters, this is the biggest mosque in Iran.

Religious activity on this site is believed to date back to the Sassanid Zoroastrians, with the first sizeable mosque being built over temple foundations by the Seljuks in the 11th century. The two large domes (north and south) have survived intact from this era but the rest of the mosque was destroyed by fire in the 12th century and rebuilt in 1121. Embellishments were added throughout the centuries.

In the center of the main courtyard, which is surrounded by four contrasting iwans, is an ablutions fountain designed to imitate the Kaaba at Mecca.

The south iwan is highly elaborate, with Mongol-era stalactite moldings, some splendid 15th-century mosaics on the side walls and two minarets.

The north iwan is noteworthy for its monumental porch with the Seljuks’ customary Kufic inscriptions and austere brick pillars in the sanctuary.

The west iwan was originally built by the Seljuks but later decorated by the Safavids. The mosaics are more geometric in style here than those of the southern hall.

Vank Cathedral

Built between 1648 and 1655 with the encouragement of the Safavid rulers, Kelisa-ye Vank in the Armenian neighbourhood of Jolfa is the historic focal point of the Armenian Church in Iran. The sumptuous interior is richly decorated with restored wall paintings full of life and colour, including gruesome martyrdoms and pantomime demons. The highlight of the museum (separate admission IR80,000) is a fabulous collection of illustrated gospels and Bibles, some dating back as far as the 10th century.

Appropriate to a city of miniature painters, relatively recent gifts to the museum include a prayer written on a single hair that is possible to see only with the aid of a microscope and one of the world’s smallest prayer books.

Isfahan Photo Gallery

General Info

- Population: 2,101,220

- Area: 551 km2 (213 sq mi)

- Elevation: 1,574 m (5,217 ft)

- Climate: Desert

- Avg. Annual Temperature : 15.6 °C

UNESCO Heritages

- Chehel Sotoun

- Masjed-e Jāmé of Isfahan

- Naqsh-e Jahan Square

- Culture

A unique Persian culture tour

Have a unique experience of exploring the rich Iranian culture with this Iran tour package. Furthermore, this Iran tour needs 11 days to show you the most famous historical sites in Iran. During this Iran travel tour, you will visit great cultural cities of Iran including Isfahan, Tehran, Kashan, Yazd, and Shiraz.

- 11 Days

- 4 Seasons

- Phys. Rating: 1 out of 5

- Adventure & Culture

Ski through Iran's culture

This Iran tour package suits travelers planning to visit Iran in winter and spring. You will enjoy Iran ski tour in Iran’s best ski resorts, will experience a touch of Iran desert tour in deserts around Kashan and Isfahan and of course you will explore Iran history by visiting the most prominent cultural destinations.

- 14 Days

- Jan. to May

- Phys. Rating: 3 out of 5

- Adventure & Culture

A two-week tour of culture and adventure in Iran

Mountains and monuments Iran tour is the most inclusive adventure and culture Iran tour packages. This mixed Iran tour includes summiting Damavand and Alamkuh as well as the Caspian Sea. Furthermore, this popular Iran travel tour shows you different aspects of Iran in only two weeks.

- 14 Days

- Jun. to Oct.

- Phys. Rating: 4 out of 5

- Culture

A five-day trip of the Iranian culture attractions

This Iran tour package is the best choice for those who have a short time for exploring the Iranian culture. So, spend only five days with this Iran tour to visit all the must-visit attractions in Iran. This short time Iran travel tour includes visiting Tehran, Kashan, and Isfahan.

- 5 Days

- 4 Seasons

- Phys. Rating: 1 out of 5

- Culture

Explore the Iranian culture in two weeks

Enjoy spending time in the historical cities of Iran and visiting their cultural attractions thoroughly with this Iran travel tour. Spend only two weeks with this Iran tour to see the most important cultural cities of Iran. Moreover, optimized Iran tour package includes visiting Tehran, Kashan, Isfahan, Yazd, and Kerman.

- 14 Days

- 4 Seasons

- Phys. Rating: 1 out of 5

- Culture

Exploring Iran thoroughly and completely

The best Iran tour for those who have enough time and want to explore Iran completely. During this Iran travel tour, you can visit Tabriz, Ardabil, Rasht, Qazvin, Hamedan, Kashan, Yazd, Shiraz and… By joining our most comprehensive Iran tour package you can visit all of the important cities of Iran.

- 21 Days

- 4 Seasons

- Phys. Rating: 1 out of 5

- Culture & Adventure

A journey to the amazing cities of western Iran

Enjoy visiting historical western cities of Iran with this Iran tour package. This Iran travel tour includes visiting Qom, Lorestan, Susa, and Isfahan. So, spend 13 days with this Iran tour to explore the rich culture of Iranian western cities thoroughly.

- 13 Days

- 4 Seasons

- Phys. Rating: 1 out of 5

- Adventure & Culture

Desert Path to Ancient Persia

A culture and adventure mixed tour including both sightseeing in the historical cities of Iran and surfing in the deserts. This comprehensive Iran tour includes visiting cities such as Tehran, Kashan, Isfahan, Yazd, and Shiraz. Also, we will pay a visit to deserts such as Maranjab, Ring-e Jenn, and Mesr. So, don’t miss this tour if you have an interest in both sightseeing and desert trekking.

- 14 Days

- Oct. to May

- Phys. Rating: 2 out of 5